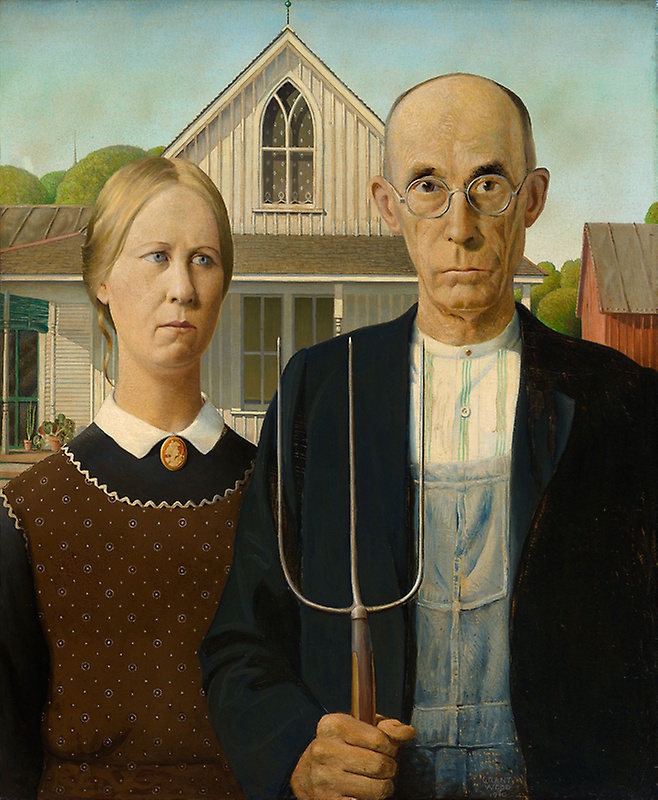

American Gothic, 1930 by Grant Wood. All rights reserved Wood Graham Beneficiaries/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

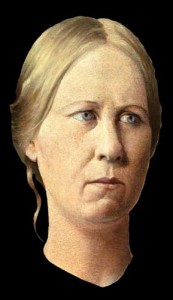

When viewing the painting, it is important to realize the extent to which Wood designed and conceptualized American Gothic. At first look, many believe American Gothic is a realistic painting, and in a sense this is true. Looking at the painting and then at the actual house, which was the model for the painting, it is clear Wood rendered a realistic version of the house. Similarly, Wood’s two models, his sister Nan Wood Graham and his dentist Dr. B.H. McKeeby, are realistically recreated, although when viewing a photograph of Nan, it can be seen his sister’s face is somewhat elongated.

Wood’s free use of “reality” can also be seen by the addition of a barn and by creating a scene—a man and woman posed in front of the house—which never occurred. The models for the artwork never posed together when they were drawn prior to, or during the painting of American Gothic.

THE HOUSE

Early pencil sketch of American Gothic by Grant Wood, featuring the farmer holding a rake instead of a pitchfork, and the caption of “American Gothic” at the bottom. (© Estate of Grant Wood/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY)

Although Wood had intended for some time to do a “portrait” of Midwestern “types,” it is known that the house in Eldon, Iowa inspired the painting Wood called American Gothic, because only the house is shown in surviving preliminary sketches for the painting.

Another early sketch places a man and woman in front of the house, very similar to the final composition. Wood’s selection of this arrangement may have been based on the late nineteenth and early twentieth century practice of traveling photographers posing subjects in front of their homes.

The choice by either the homeowner or photographer as to where the people stood, testifies to the association Americans have with their homes as extensions of themselves. In rural America, a home not only signified family but also the mutual hard work of its members, and as the family’s greatest financial possession.

Wood, who rarely explained his work, did not clarify his choice of this house. Was he mocking the inclusion of this window as a homeowner’s choice to make an ordinary house look grander than it was? Or was he honoring the effort the homeowners took (and the additional expense they incurred), to make an artistic statement that was not otherwise needed? No one knows for sure. But it is true that the choice was not made by chance. Wood used his compositional elements with such care that some importance is attached to his choice of the house.

The John Curry homestead near West Union, Custer County, Nebraska, 1886, by Solomon D. Butcher, photographer. (More info.)

THE WINDOW

Important compositional elements of the painting are based upon the window. It has two equal arches, capped by the oddly shaped pane that joins them together from the top.

Looking at the painting in its entirety, the window is duplicated with the two halves of the window repeated by the two human figures standing side by side The roof of the house visually joins the man and woman in the same way that the oddly shaped top pane of glass joins the two arches of the window.

THE HAYFORK

In a surviving pre-painting sketch, the male figure holds a rake rather than the three tined hayfork of the painting. Again, this cannot have been an idle choice. Scholars, knowing Wood’s antic sense of humor, speculate endlessly on the significance of the hayfork. Is it an allusion to a devil’s pitchfork or something less sinister? If Wood was making such a statement, he kept it to himself.

One thing that is clear is that he regarded the shape important enough to reinforce it by repeating it in the stitching on the male figure’s bib overalls (continuing into the pattern of his shirt). It also functions compositionally, as it mirrors (upside down) the shape of the panes in the upstairs window. This kind of repetitive pattern enlivens the composition and gives it rhythm.

THE PLANTS

Sansevieria (also known as a snake plant or mother-in-law’s tongue).

The plants on the porch of American Gothic.

Beefsteak begonia.

The plants were not on the porch of the house when Wood created his sketches. Why include a beefsteak begonia and a mother-in-law’s tongue (Sansevieria)? Wood did not disclose the reason for his choices, but plants often have symbolic meanings.

According to the language of flowers, the begonia (which, in this painting, some have mistaken for a geranium), can sometimes symbolize impending misfortune, caution, dark thoughts, gratitude, individuality and uniqueness, or even justice and peace. Whether these meanings apply still to specifically a beefsteak begonia, or whether Wood even had any interest in the language of flowers, is unknown.

Wanda Corn, a leading scholar on Wood and author of Grant Wood: The Regionalist Vision, has speculated that the hardiness of Sansevieria made it popular with pioneer women and his use of the plant may be no more than an allusion to the hardiness of those women.

Whatever the plants may symbolize they do contribute to the composition: the beefsteak begonias echo the shape of the trees behind the house, the three leaves of the mother-in-law’s tongue repeat once again, on a smaller scale, the pattern of the window, the hay fork, and the stitching on the bib overalls.

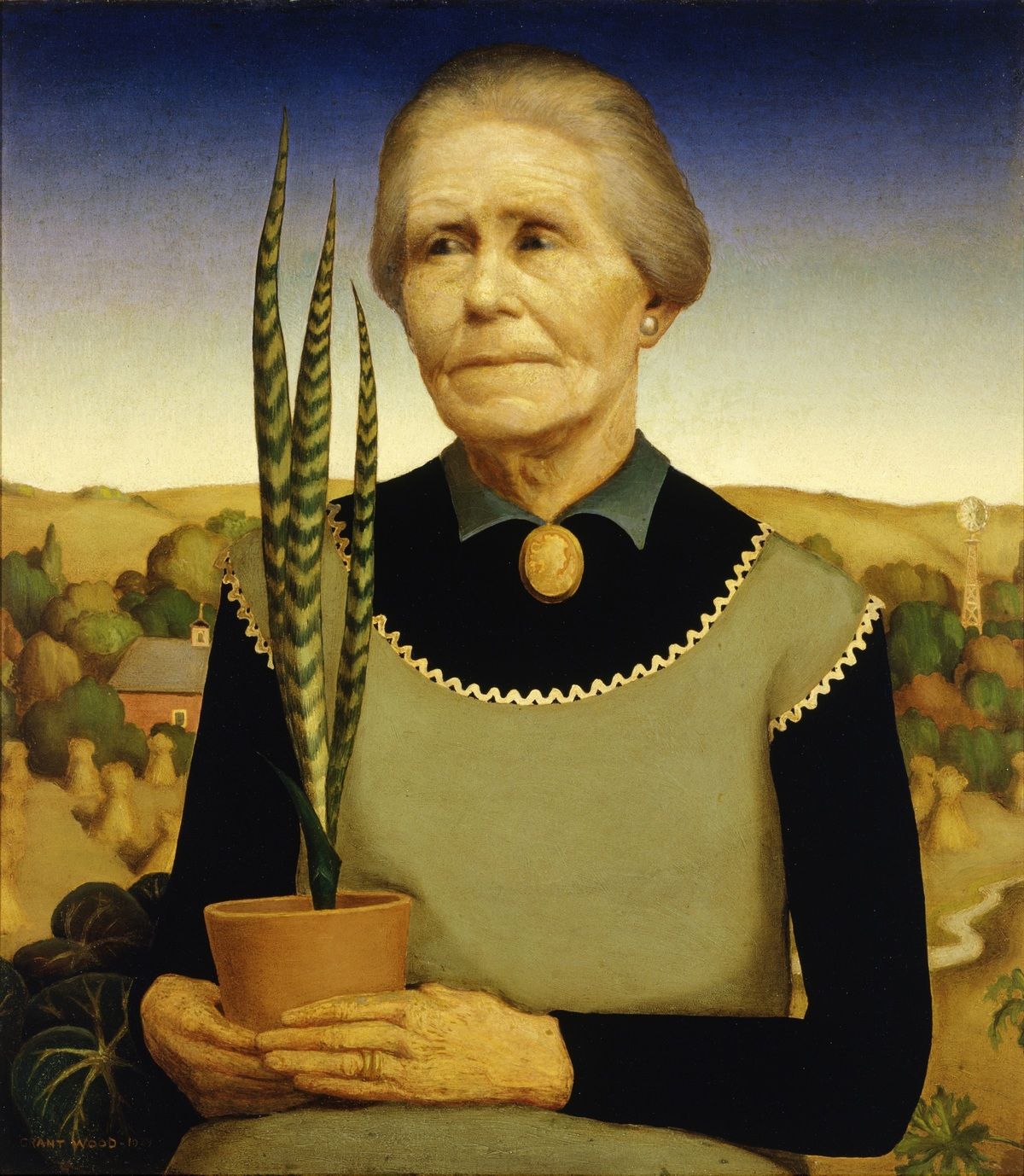

Moreover, the same plants appear in the portrait Wood painted of his mother in 1929. In Woman with Plants, his mother sits in front of a beefsteak begonia that, as in American Gothic, echo the tree shapes in the background. She holds a potted mother-in-law’s tongue in front of her. Reusing elements from one painting to the next is common in Wood’s work and if the plants had symbolic meaning in addition to their compositional importance, that too carried from painting to painting.

THE PATTERNS

The continuity of other patterns also ties the composition together. Most notable is the pattern on the curtains in the upstairs window and the similar pattern on the woman’s apron. It is worth noting that these are pure pattern, both the curtain and apron lack the distortion that would realistically occur from folds in fabric.

Among the other many repetitions of patterns is the repetition of vertical lines, particularly visible in the hayfork, white shirt, overalls, and the battens on the house and barn in the background.

It is worth noting the rickrack edging on the apron of American Gothic’s female figure is found on his mother’s apron in Woman with Plants, and both women wear a cameo brooch.

THE EXPRESSIONS

Described as dour, even ill-humored, which seems at first to contradict Wood’s claim that he was painting an “affectionate portrait” of Midwestern types. The man and woman (in one rare explanation Wood claimed they were father and daughter) seem to be “no nonsense” characters. An explanation for the stoic expressions may come from early photographs. Photographers discouraged models from smiling because of the film’s need for long exposure times. Therefore, borrowing from that photographic practice would result in unsmiling faces.

Adding a human touch softens the sternness of the subjects. An errant curl that hangs down behind her right ear softens the severity of the woman’s hairdo. The man’s gold collar button is a bit on the showy side for someone we otherwise take to be a sober, conservative man.

Do we really know how Wood feels about his creations? It seems unlikely that he is holding them up for ridicule; it seems more likely that Wood had mixed feelings about the people he sought to portray.